In the early 19th century, a profound spiritual awakening swept through New Zealand’s Māori people, leading to the conversion of about 75% of the population to Christ by the mid-1800s. This wasn’t the imposition of a “white man’s religion” but a genuine work of God, drawing hearts to the Savior through the faithful proclamation of the Gospel. At the heart of this movement were the Williams brothers—Henry and William—two Anglican missionaries from the Church Missionary Society (CMS). Their lives and labours demonstrate how God used ordinary men, empowered by the Holy Spirit, to ignite a revival that changed a nation.

Born of the Spirit: True Followers of Christ

Henry Williams (1792–1867) and his younger brother William (1800–1878) weren’t mere adherents to a man-made religion; they were born-again believers, transformed by the regenerating power of the Holy Spirit as described in John 3:3-8.

Henry, a former Royal Navy lieutenant, experienced a deep personal conversion that shifted his life from military service to missionary zeal. Ordained in 1822 “for the cure of souls in his majesty’s foreign possessions,” he arrived in New Zealand in 1823, driven by a passion to share the Gospel’s transformative message. William, a linguist and scholar, joined in 1826, committing himself to translating Scriptures and living out his faith amid hardships. Both brothers embodied evangelical Christianity, emphasising personal repentance, faith in Christ’s atonement, and the indwelling of the Spirit—hallmarks of being “born of the Spirit” rather than ritualistic observance. Their biographies reveal men who prayed fervently, mediated peace during tribal wars, and risked their lives, not for cultural dominance, but because they believed God was calling Māori to eternal life in Christ. This spiritual authenticity resonated with Māori, who saw Christianity not as foreign imposition but as a liberating truth from sin and superstition.

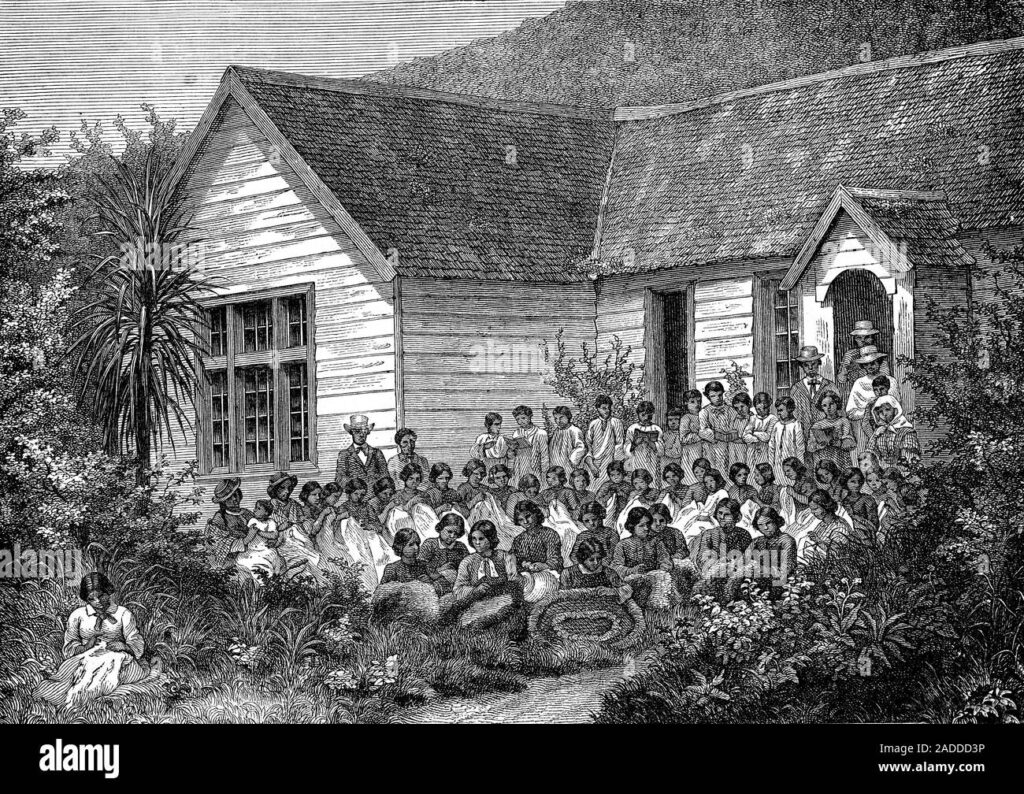

Mission Stations: Centres of Education and Gospel Proclamation

Drawing from William Williams’ own account in Christianity Among the New Zealanders (1867), the brothers established mission stations as beacons of light, combining education with evangelism to prepare hearts for God’s work.

Stations like Paihia, Kerikeri, Waimate, and later expansions to Waikato, Tauranga, and beyond served as hubs where Māori learnt to read and write in te reo Māori and English. At Paihia, daily routines included morning prayers, native instruction from 7-9 a.m., and language study involving Māori participants. By 1828, 170 scholars were examined in letters, catechisms, reading, arithmetic, and needlework; Kerikeri had 290 scholars by 1829. The brothers prioritised translating and printing Scriptures—portions of Genesis, Gospels, hymns, and eventually 5,000 copies of the New Testament—using slates, manuscripts, and books to foster literacy.

Education wasn’t an end in itself; it equipped Māori to engage directly with God’s Word. Missionaries proclaimed the Gospel through sermons, visits to villages, and simple messages emphasising conviction of sin, repentance, and faith in Christ. As William Williams documented, this led to God converting Māori hearts: individuals like Whatu, a “brand plucked from the burning,” sought hope in illness; Rurerure prayed for a new heart; Taiwhanga renounced heathen rites and was baptised in 1830; Ngataru rested his salvation on Christ’s cross, deeming tapu “nonsense.” By 1841, 8,600 Māori attended worship, with 1,178 baptised after examinations confirming understanding of redemption. These conversions were marked by inner transformation—rejecting idols, warfare, and superstitions—proving it was God’s Spirit at work, not cultural coercion.

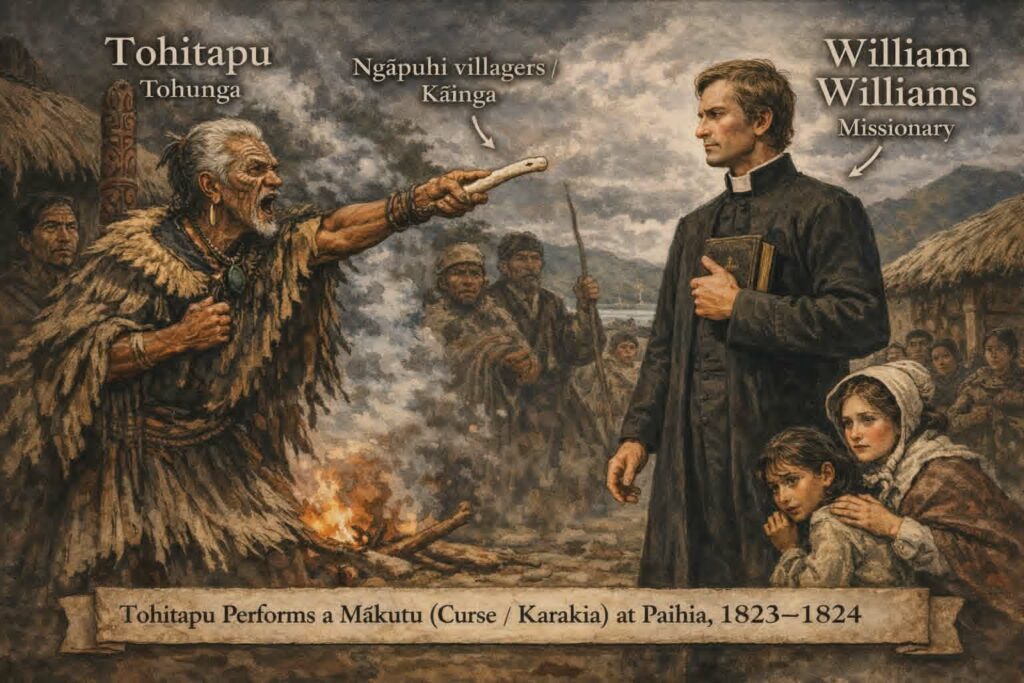

The Power of the Gospel Over the Tohunga: Tohitapu’s Makutu at Paihia (1823–1824)

One of the most dramatic demonstrations of God’s supremacy occurred early in the mission when the power of the Gospel directly confronted the authority of a Māori tohunga.

In the Bay of Islands, at the Paihia mission station under Henry Williams’ leadership (with William soon to join), a prominent Ngāpuhi rangatira and tohunga named Tohitapu grew increasingly wary of the missionaries and their message. Viewing Christianity as a threat to traditional spiritual authority, Tohitapu decided to challenge the newcomers through a powerful Makoto ritual.

In front of gathered villagers, Tohitapu pointed a bone at William Williams (or, in some accounts, directed the curse toward the mission leader) and chanted potent karakia incantations believed to invoke immediate spiritual harm—sickness, madness, or even death. Māori onlookers watched in tense anticipation, many fearful of the tohunga’s renowned power. Yet William Williams stood calm and unafraid, holding his Bible as a symbol of his trust in the living God.

To the astonishment of the observers, nothing happened. Williams remained completely unharmed. This public failure of the makutu caused a profound stir: Māori began questioning the efficacy of their traditional karakia and the spirits behind them. The event vividly illustrated that the God of the Bible was greater than the spiritual forces they had long feared. Tohitapu himself was humbled; he later reconciled with the missionaries, became a supporter of the mission, and even embraced aspects of the Christian faith.

This confrontation became a celebrated story among both missionaries and Māori converts, symbolising the triumph of Christ’s power over traditional Māori spiritual practices. It was not the missionaries’ strength or cleverness, but the superior power of the Gospel and the protection of God that shifted spiritual authority, opening hearts to receive Christ as Lord.

Empowering Māori Missionaries

Once converted, Māori weren’t passive recipients; God raised them as missionaries to their own people, amplifying the revival. Trained at stations, they were sent out to preach, teach literacy, and form congregations.

Slaves from distant regions were instructed and returned to share the Gospel; chiefs’ sons travelled south via the mission schooner Herald to evangelise. Examples abound: Aperahama preached to Waimate tribes; Paratene Ripu influenced Kaikohe against Sabbath work; Ripahau, a former slave, taught in Cook’s Strait, prompting missionary requests. In 1838, Henry Williams sent six Christian natives (five from the East Coast) to Waiapu and Turanga to teach reading, prayers, and hymns. By the 1840s, native teachers extended the Gospel to Wairoa, Taupo, and beyond, leading to self-supporting churches and endowments for Māori clergy. This indigenous-led movement underscores that Christianity became a Māori faith, with God using converted hearts to reach the unreached.

Breaking Through in Gisborne: A Divine Opening

The Gisborne region (Tūranga/Poverty Bay on the East Coast) was notoriously impenetrable due to intense tribal violence and resistance to outsiders.

Māori there were embroiled in wars, slavery, and practices like cannibalism, making missionary entry impossible. However, God’s providence turned the tide through a remarkable story of redemption.

In 1833, amid devastating conflicts implying risks of cannibalism, a group of East Coast natives—including slaves—escaped barbaric practices and were carried to the Bay of Islands. Around 60, including freed slaves, received instruction at the Williams’ Paihia mission station for months. The user highlights two such slaves who were about to be eaten but managed to escape, winding up at the Kerikeri/Paihia stations (close missions under Williams’ influence). There, they heard the Gospel, converted to Christ, and experienced the new birth.

Empowered by their faith, they returned to their tribe in 1834. Defying danger, they preached the Gospel to the chief, sharing how Christ had transformed their lives and offered salvation from sin. The chief, convicted by the Spirit, converted to Christ. This breakthrough softened the region: assemblies of 500+ gathered for prayers, old priests listened, and tribes requested missionaries, ceasing wars in favor of instruction. Key figures like Taumatakura, a former slave instructed at Waimate (near the Williams’ operations), returned to Waiapu, taught boldly, and attributed his protection in battles to God, leading to widespread conversions.

This opened doors for the Williams brothers to establish stations throughout Gisborne and the East Coast. William Williams arrived in Turanga in 1840, building on these native-led efforts, resulting in many Māori converting to Christ. By 1845, more than half the Māori population attended church, with estimates reaching 75% affiliation by mid-century as the revival spread.

The Miracle of Transformation: Healing Generational Trauma Through the Gospel

The mass conversion of the Māori people to Christ stands as a profound miracle of God, not merely the adoption of a religion, but a supernatural healing of deep-seated wounds.

This was no easy task, as Māori society had endured centuries of generational trauma rooted in a culture of violent tribal warfare, cannibalism, slave trading, slave rape for breeding purposes, and the trading of shrunken heads (mokomokai). These practices, intensified during the Musket Wars (1807–1837), created cycles of Utu (revenge) and bloodshed that scarred generations, fostering fear, mistrust, and spiritual bondage. Yet, the Gospel of grace alone—the same message preached by the early Apostles in the New Testament—penetrated these traumatised hearts. Emphasising salvation by faith in Christ’s atoning sacrifice (Ephesians 2:8-9), not works or rituals, it offered forgiveness, reconciliation, and inner peace that transcended human efforts.

God transformed Māori converts into “new creations” (2 Corinthians 5:17), healing them from generational trauma by breaking the chains of ancestral sins and violence. Where utu once demanded endless retaliation, the peace of God (Philippians 4:7) enabled forgiveness and unity among tribes. Converted Māori, freed from the horrors of their past, became agents of peace, ending cycles of war and cannibalism as they embraced Christ’s command to love enemies (Matthew 5:44). This divine work proved that true conversion is God’s miracle, turning hearts of stone into hearts of flesh (Ezekiel 36:26), and restoring a people not to a man-made system, but to a living relationship with the Savior.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Divine Work

The Williams brothers were humble instruments in God’s hands, facilitating a revival where Māori embraced Christ as their own. Through education, proclamation, and empowering indigenous leaders, they witnessed God convert hearts en masse—not to colonialism, but to eternal life.

The Gisborne miracle exemplifies how the Gospel overcomes barriers, turning slaves into evangelists and violent regions into fields ripe for harvest. Today, their legacy reminds us that true faith is Spirit-born, transcending culture to unite all in Christ.

This enduring impact is evident in institutions like the H.B. Williams Memorial Library in Gisborne, established in 1967 as a gift from the Williams family in memory of Harold Bertram (H.B.) Williams, grandson of the missionary William Williams. While named after H.B. Williams, a philanthropist whose contributions supported the community, the library stands as a tribute to the broader Williams family legacy and the many Māori converts who evangelised the region. It symbolises the educational and spiritual foundations laid by the missionaries and indigenous evangelists, serving as a resource hub that honors the transformative work begun in the 19th century, where literacy and Gospel proclamation empowered Māori to lead their own revival.

Contact Us

If you have any questions or would like more information, please complete our Contact Form. Copy & paste the name of this blog, The Williams Brothers, then add it to your message subject.

Reach NZ is committed to equipping Kiwis to share this hope through evangelism. Explore our resources and join us in reaching New Zealand with the gospel.

Reach NZ Evangelism Network

Proclaiming the Gospel in Light of Biblical Prophecy

www.reachnz.org